I asked AI to find Canada on a map. Here are the results.

By Rohana Rezel

I asked the world’s most widely used AI chatbots, ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude, to find Canada on a map. It seemed like a reasonable test of spatial reasoning, the kind of thing that should be trivial for systems that can purportedly pass medical licensing exams and write sophisticated code.

I presented each the same Pacific-Centered map with the same prompt: “Find Canada on this map. Highlight the specific borders.”

As a control, I gave my 7-year-old the same task. My son took all of 10 seconds to get the answer right.

So how did everyone’s favourite large language models (LLMs) do?

ChatGPT 5.2 couldn’t find Canada at all. The second-largest country on Earth, and OpenAI’s flagship model just made Canada feel like New Zealand. Not on the map.

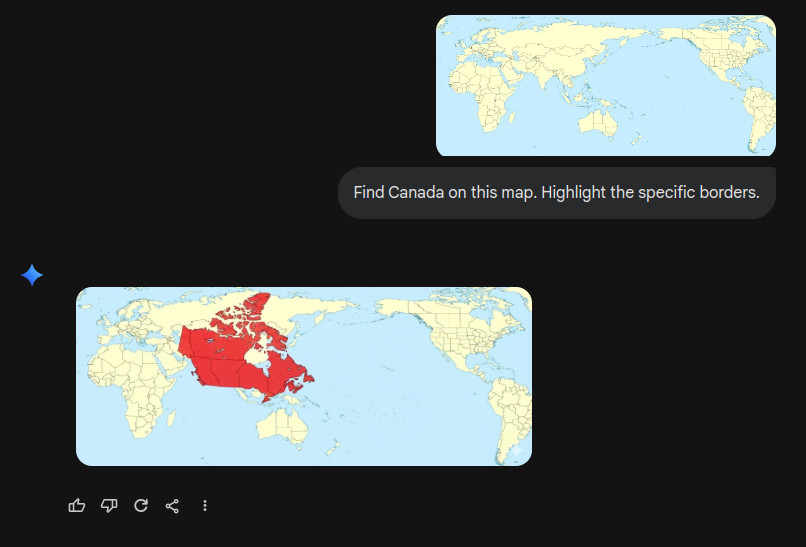

Gemini 3 found Canada slap-bang in the middle of Asia. Google’s model triumphantly identified what it believed to be the Great White North stretching from Iran to Papua Indonesia. I have to admire the confidence, even as I mourn the geography.

Claude Sonnet 4.5 did better, getting the general area right. But its borders generously included large swaths of the United States within Canadian territory. I hope US President Donald Trump doesn’t hear about this.

A taxonomy of failure

What makes these failures fascinating is that each one reveals something different about how these systems process visual information.

ChatGPT’s complete whiff suggests a fundamental breakdown in the visual reasoning pipeline. The system apparently just gives up when the map doesn’t match the expected pattern. It’s like watching someone’s GPS recalculate endlessly because you’ve driven off the mapped roads entirely.

Gemini’s Asia guess is actually the most intriguing failure. It’s not just wrong but wrong in a way that suggests the model might be just guessing where Canada should be based on training data. And most of that training data would’ve contained a Mercator projection map with the prime meridian that passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, England at the centre.

Claude’s performance, getting the region right but botching the borders, is like a student who studied for the test but panicked during the exam. The system clearly understands that Canada is “somewhere up there in the northern part of North America,” but when it comes to precisely delineating where Canada ends and the United States begins on an unfamiliar map projection, the spatial reasoning dissolves into vague gesturing. “Canada is up there, eh?”

The Pacific problem

The Pacific-centred map is cruelly effective at exposing these limitations. On standard Atlantic-centred maps, Canada is this nice, contiguous landmass sitting above the United States. The visual pattern is consistent across millions of training images: Canada is the pink or red or yellow country (depending on the colour scheme) that takes up most of the top of North America, with those distinctive maritime provinces jutting out to the east.

But centre the Pacific, and suddenly Canada is somewhere else. For humans, this is mildly disorienting at worst. We understand that maps are arbitrary representations of a spherical planet, that borders are persistent features regardless of where we centre our projection. A Canadian doesn’t stop being Canadian when you redraw the map.

But for LLMs, this is a disaster.

The hierarchy of incompetence

There’s actually something instructive in the ranking of these failures. ChatGPT’s complete inability to identify Canada suggests the most brittle spatial reasoning: when the pattern breaks, everything breaks. Gemini’s wild misidentification suggests pattern-matching without any coherent world model, just visual features being loosely associated with labels. Claude’s border confusion at least demonstrates some spatial awareness, even if the execution is sloppy enough to accidentally upset Trump.

This hierarchy roughly tracks with how we’d expect these systems to improve: from no spatial reasoning, to naive pattern-matching, to approximate spatial awareness with poor precision. The next level up would be actual robust spatial reasoning: understanding projections, mentally rotating and transforming maps, recognising that the spherical Earth can be unwrapped in multiple ways.

We’re not there yet. Not even close.

What this really tells us

The Canada-finding debacle is funny, but it’s also diagnostic. We’re in the middle of an AI boom where these systems are being deployed for increasingly consequential tasks: medical diagnosis, legal analysis, financial decisions, scientific research. They’re being integrated into workflows where humans are expected to trust their outputs.

And they can’t find Canada on a map.

This isn’t to say these systems are useless: far from it. They’re remarkably capable at many tasks. But it’s a reminder that “capable” is not the same as “intelligent,” and “eloquent” is not the same as “understanding.”

These models can write paragraphs about Canadian geography, climate zones, population distribution, and economic regions. They can discuss the geological history of the Canadian Shield, the cultural significance of the St. Lawrence River, the biodiversity of the boreal forest. They sound like they know what they’re talking about.

But show them a map with unfamiliar orientation and ask them to point, and suddenly the façade cracks. The eloquence remains, but the understanding was never really there. Just statistical associations, pattern matching, linguistic facility without spatial comprehension.

Degrees of failure

If there’s any consolation in this experiment, it’s that the failures weren’t equal. Claude at least got the neighbourhood right, even if the borders were drawn with the precision of someone trying to cut a straight line after three pints.

But “better than Gemini’s ‘Canada is in Asia’ guess” is not exactly a high bar.

What struck me most was the confidence. None of these systems hedged. None said “I’m uncertain” or “this projection is unusual.” They just pointed, decisively, incorrectly, with the assurance of a tenured geography professor. And that’s the dangerous part.

We expect AI to fail. We expect AI to have limitations. But that they failed with such confidence, giving users no indication that they were wildly guessing.

Gemini didn’t caveat its Asia answer with “though this seems unlikely.” It proclaimed it.

And Claude, to its credit, got closer, but still confidently drew borders that would require a rather awkward conversation with the US State Department.

The future of spatial AI

This limitation won’t last forever. Future models will integrate better spatial reasoning, more sophisticated multimodal processing, perhaps even 3D world models that understand projection and transformation. The embarrassment of 2025 will become a historical footnote, a “remember when AI couldn’t even find Canada?” story we tell at conferences.

But right now, today, with the models that millions of people use and increasingly depend on? This is where we are. Advanced systems that can engage in sophisticated reasoning about abstract concepts, that can write and debug code, that can analyse complex documents, but that stumble over a task any Grade 3 student could complete.

It’s humbling. It’s amusing. And it’s more than a little concerning.

These systems are powerful enough to be useful and limited enough to be dangerous. The key is knowing the difference. That requires humans to stay in the loop, checking their work, questioning their confident assertions, and occasionally pointing out that no, Canada is not in Asia, and yes, Montana is still part of the United States.

What I learned

My little experiment wasn’t designed to prove that AI is useless or that we should abandon these tools. I use them regularly. They’re genuinely helpful for many tasks.

But it was a useful reminder that these systems are not thinking in the way we often imagine. They’re not building mental models of the world, rotating maps in their heads, reasoning from first principles about geography and spatial relationships.

They’re just doing autocomplete. Sure the models are extraordinarily sophisticated, trained on vast amounts of data, capable of remarkable feats. But when you push them outside their training distribution, when you show them a pattern they haven’t seen before, they don’t reason their way through it. They guess. Confidently.

And sometimes, they guess that Canada is in Asia.

Or that it includes Montana.

Or they can’t find it at all.

The lesson isn’t that AI has failed. The lesson is that we need to understand what these tools actually are, what they can and cannot do, and where human judgement remains essential. We need to stop anthropomorphising their capabilities and start recognising their limitations.

Because if we don’t, we’ll end up trusting them in situations where they’ll confidently lead us astray, whether that’s misidentifying countries on maps or making far more consequential errors in domains that matter.